sunflower on Sarah's grave, dying in fall

sunflower on Sarah's grave, dying in fall The air is taking on that fall feeling. Cool nights filled with cricket song giving way to warm days. My garden is speaking of fall too. Sunflowers bent over heavy with seed and the last of the sweet cherry tomatoes ripening on the vine.

Fall is the season of brilliance. The quality of light holds a particular crisp golden shimmer that I never tire of. In another month the sunflower seeds left behind by the birds and squirrels will be on the ground and the leaves will begin to turn themselves into a blaze of color before they too float to the ground. Fall, in all its brilliance, is the season of death. The earth makes no argument against it. There is no attempt to avoid it or cover it up. Everything simply sheds itself in a rush of beauty.

What if we allowed ourselves to turn toward dying the way the earth does, when our time comes? Might we also discover or taste a kind of brilliance? My story is about the grace of turning toward death with my beloved partner Sarah. I share it in hopes of casting seeds of encouragement to others. Facing into death and the storms of grief have much to teach us about life.

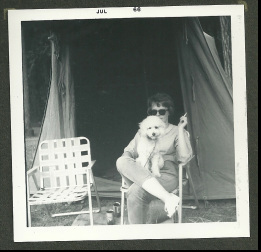

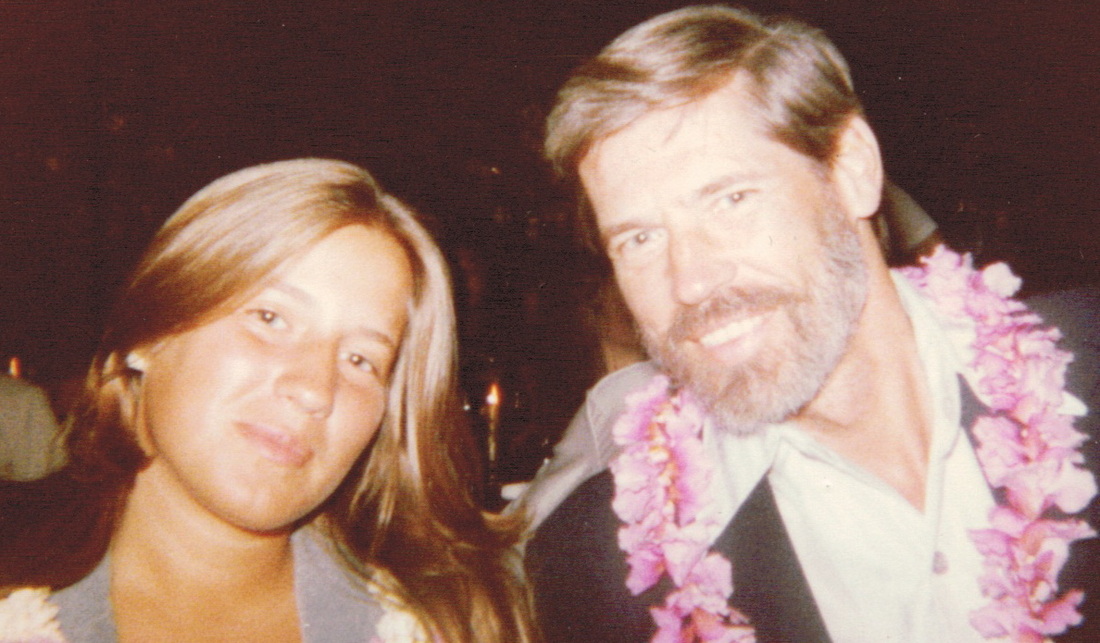

Carrie (left) + Sarah

Carrie (left) + Sarah Sarah and I had many conversations about death in those five years. They were never easy conversations. There were times when we fell to the ground in sorrow knowing we would likely have to say our goodbyes. Meeting this sorrow together in the open offered a kind of tenderness and love that was so alive and remains powerfully with me now. This intimacy with death allowed us to treasure the simple moments that life offers. Morning tea time on the couch by the woodstove often felt like a feast. The sweetness of time, the warmth of tea and fire and the chance to honor together a new day were gifts and we knew it. Living for a time in this knowing illumines life as the gift it is.

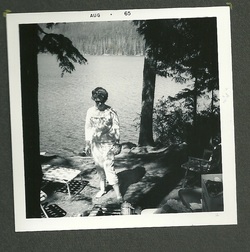

When our goodbye time came in late summer two years ago we savored each moment and made sure to take our time with it. We acknowledged together our last time going to the movies with our kids. Our final outing together was a visit to the green cemetery where Sarah would be buried. We wandered the fields together and she told me she wanted to be buried in the open part of the field because she loved the open. We took time there to sit and read Mary Oliver poems together and choose two that would be read at her memorial service. This slow and deliberate goodbye dance broke my heart wide open. In so doing, it offered me a way to hold all that was to come.

To love what will not last is food for the soul because it is how it is. Everything I see from my chair here by my garden tells me this is how it is. Next year’s sunflowers will not be the same ones that are here now. The soil of life needs the dying in order to continue nourishing life. The sorrowing heart needs the mysterious force of grief to keep itself alive. We live in a culture that tells us otherwise. That tells us to deny death and skip as quickly as possible over grief. Sarah’s dying time was a gift just as her life was to all who knew her. I thank her every day for teaching me how big love can be and how precious this human life is.

Sarah chose to be buried at Greensprings, a Natural Cemetery Preserve outside Ithaca, New York. She wrote the words that are on her grave marker in a journal book when she and Carrie were visiting the cemetery together two weeks before she died. Sarah's son chose these words from the journal and engraved the stone. This act of devotion and craftsmanship was his graduation project from high school.

You may post comments for Carrie here or reach her at carriejst at gmail.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed