Daddy's Girl

Daddy's Girl I’ve heard it said that forgiveness is a process, not an act. In my case I recognized the process only once it was complete.

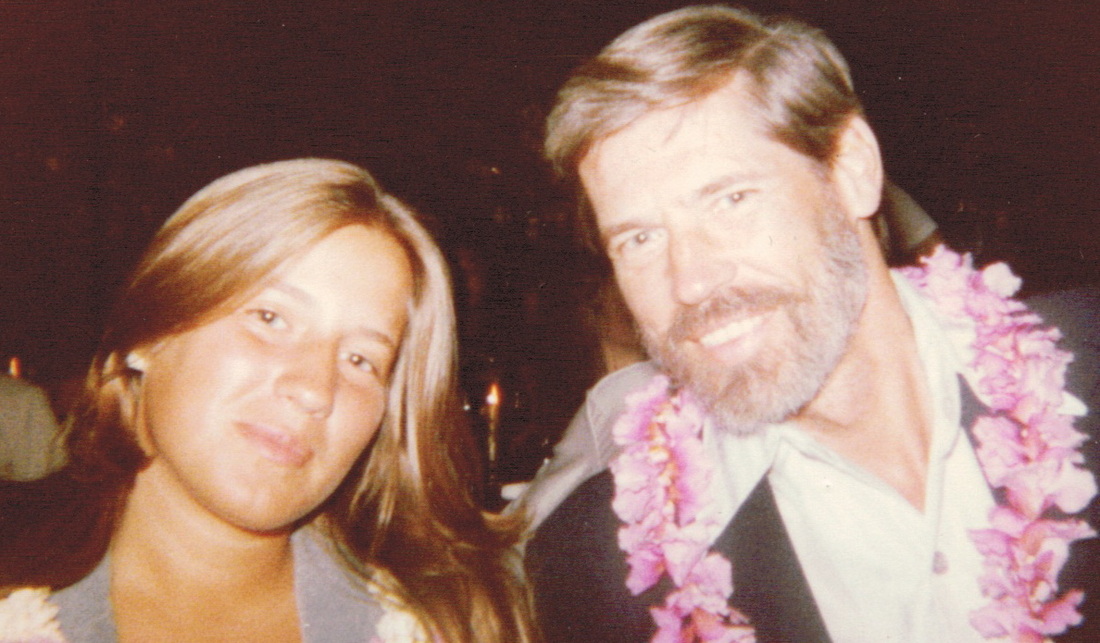

I had held it together during those precious months when my father and step-mother's needs were at long last congruent with my desire to be family with my father. But when it was over, I needed an outlet for the hurt I still felt over his repeated abandonment; for the fear I felt throughout this, my first real confrontation with mortality.

My father hadn't wanted a funeral, according to my step-mother - and she couldn't handle one more thing. I received a yoghurt container with a portion of his ashes, his veteran's flag, a threadbare B Kliban cat t-shirt I'd given him 25 years earlier, and other mementos of his life. I decided to organize a backyard memorial service of my own.

I'd completed all the logistical planning, determined the elements of the ceremony. Only one piece remained: clarifying what I needed to say to my father through this memorial, what I needed to embrace and to release. I planned a two-day retreat to the Oregon coast where I would immerse myself in the remnants of my life with my father - the letters we'd exchanged, the family story interviews I'd done with him in graduate school, photos, journals.

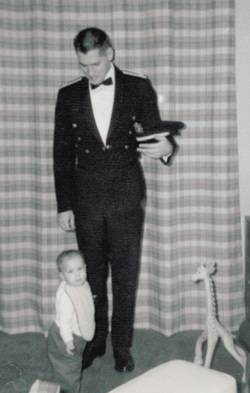

I asked my mother to be there for me, a primal "I want my mommy!" impulse as I faced my grief. As soon as we settled into our motel room I feared I'd made a huge mistake. We had shared the loss of my father from the very first, when he brought us home from the hospital after my birth, left the car running, and went immediately back to work. But she, of course, had her own experience of this man - her first love, her husband of 15 years, the father of her children whom she'd seen only twice after their divorce, who had refused her request to say good-bye once diagnosed with terminal cancer. Our feelings about this man, loving and losing him, had been so enmeshed for so many years, could I step into and through my own process in her presence?

Without needing to discuss it, my mom wisely headed out to the porch looking out to the sea. She sat with her back to me reading as indoors I spread all of the artifacts out on the bed and wrote and sobbed my way to what I knew to be true. When I finished, she came inside. I read what I had written to her.

Among the things I was ready to say to my father was: “You did the best you could.” My mom objected: No! He could have done better. He should have done better!

Yes, of course, he should have. And in theory, he could have. But what stood sturdy inside me then was not the ways I’d been hurt by his failings, but my recognition that his capacity to love had been so stunted. I remembered the story he’d told me about a contest of wills with his 1st grade teacher; he’d refused to draw because she hadn’t told him how. What first grader doesn’t know how to draw?

I felt blessed that my heart had not been similarly confined. I knew in that moment that I’d crossed a bright line from the treacherous emotional terrain I’d traversed with my mother and father, to a new, more spacious place.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed