L4: Live Life Like Leyla

L4: Live Life Like Leyla Stephen Jenkinson says, "How we die, how we care for dying people, and how we carry our dead: this work makes our village life, or breaks it."

In the last week, two posts in Facebook groups I follow have illustrated the proposition that, as Canadian death midwife Sarah Kerr puts it, "The mark of a good death is that it's a village-making event."

Sarah's observations, and her work, are described in A Soft Goodbye, an excellent on-line article in The Walrus on "How a death midwife helped the author and her family grieve the loss of a cherished relative." Sarah continues: "Death is not a mistake. It’s not something the world shouldn’t have. It serves a purpose. And it brings people together when it’s done right.”

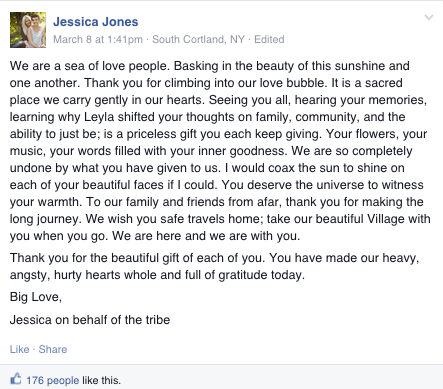

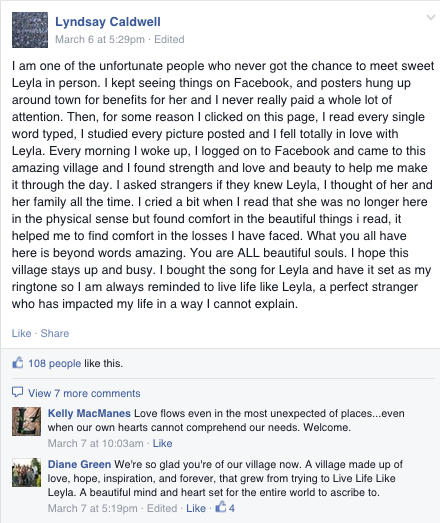

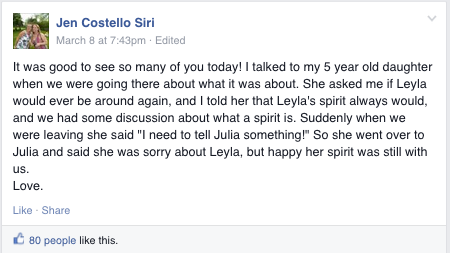

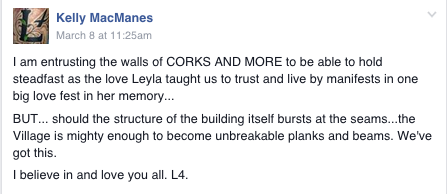

The second post came from my Orphan Wisdom classmate Carrie Stearns whose essay on her partner's death, "The Brilliance of Dying" appeared on my blog last fall. Carrie shared an article from her local paper with this note: "Here is a beautiful example of a village growing in the face of death. My daughter's class mate died this morning in her Mama's arms and the community is weeping and sharing like never before."

click image to visit Leyla's Village on Facebook

click image to visit Leyla's Village on Facebook "Leyla’s two-year long struggle with cancer has inspired countless others, including a 1,000-plus member online community called Leyla’s Village, to 'Live Life Like Leyla' and embrace all the beauty of life and set aside its trivialities and minor stresses."

In Stephen Jenkinson's small book How It All Could Be: A Work Book for Dying People and Those Who Love Them he ends with a prayer "...that your people will be blessed by your coming and your going, that ...they will marvel at your way of going out from among them, and that you might be reason enough for them to continue for a while...."

Reading some of the posts in Leyla's Village makes it clear that the manner of her death, the way she went out from among them, made a village. She indeed gave her people reason enough to continue without her, hearts broken open though they be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed