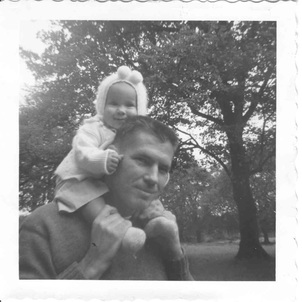

Imagined conversations, remembered conversations - my thoughts are filled with these, exchanges with my father, my Nonna, my friends Bill, Marcy, Kathy, and more.

But to speak out loud - to them, to those who came before them, whose lives collectively, cumulatively, ended up as me - is to render me shy, uncertain, inept.

I used a song to unscrew my jaw when I knew I needed to say certain things to my dad at the memorial I held for him in my backyard eight months after he died.

"Operator, well could you help me place this call? 'Cause I can't read the number that you just gave me. There's something in my eyes, You know it happens every time. I think about the love that I thought would save me."

Jim Croce (1943-1973) was the sound track to those fifth and sixth grade years when my father left us again and again for an affair he was unable to break off. And then he left for good, moving 6,000 miles away six days after his divorce from my mother was final on my twelfth birthday.

I bought two copies of Croce's Greatest Hits 25 years later when my dad was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer: one for him, one for me. Already unable to do many things for himself, he shrugged his consent when I offered to put it on the stereo. We wept through nearly every song. Those around us were badly discomfited. But I like to think that he and I, in those tear-soaked moments, were speaking the same language for perhaps the first time.

* * *

Telephone of the Wind, Otsuchi, Japan (NHK Documentary photo)

Telephone of the Wind, Otsuchi, Japan (NHK Documentary photo) A friend sent me a link to an episode of This American Life featuring a phone booth in northeastern Japan serving as a memorial to those dead (nearly 17,000) and missing (still more than 2,500) in the earthquake and tsunami. Dubbed Telephone of the Wind, it's connected (by phone company standards) to nowhere. And yet individuals of all ages and whole family groups are making pilgrimages from all over the country to stand in the structure overlooking the sea, pick up the black rotary-dial telephone receiver, and speak aloud.

"Hello. If you're out there, please listen to me."

According to one article, "The phone is owned by a 70 year old gardener named Itaru Sasaki who had installed the phone in his garden prior to the disaster in order to give him a private space to help him cope with the loss of his cousin. However after the devastation of the tsunami, news about the phone gradually spread and eventually it became a well known site with various reports suggesting that three years after the disaster it already had experienced 10,000 visitors."

Listening to the Japanese-American radio journalist translate documentary recordings of these conversations, I was struck by how hard it can be to loosen one's tongue when the listener is on the other side of the veil. Even in Japan, where the "idea of keeping up a relationship with the dead is not such a strange one," as explained by reporter Miki Meek, citing the ancestor altar her uncle maintains: "there are photos on a little platform and everyday he leaves fresh fruit and rice for them, lights incense and rings a bell. It’s a way to stay in touch. To let them know they are still a big part of our family.”

Even there, it might take a simple rotary phone to loosen the tongue, to speak words carried by breath to those who breathe no longer, but are not gone.

"But isn't that the way they say it goes? Well let's forget all that, And give me the number if you can find it, So I can call just to tell 'em I'm fine, and to show...I've overcome the blow. I've learned to take it well. I only wish my words Could just convince myself That it just wasn't real...But that's not the way it feels...No, no, no, no, no..."

For more on my journey with my father: The story of his memorial stones, how I found Forgiveness, the surprising end to his memorial ceremony, marking the 10-year anniversary of his death, the belated eulogy I wrote for him, the raspberries that always remind me, and what I did with his veteran's flag.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed