Photo: Chuck Nakell, Portland Audubon

Photo: Chuck Nakell, Portland Audubon Last week, the sound of grief ruptured the quiet of our Sunday morning: my spouse Amber reacting to the call from the hospice house. Her Dad had just died.

The days leading up to and following his last exhale were punctuated by so many clear notes of grace. One of those came in the form of a glossy, black bird.

On Wednesday morning, at the time Dean's body was being cremated, Amber and I entered the wet green womb of the Portland Audubon Sanctuary, where Dean had volunteered for 17 years. On this rain-soaked weekday, we had the place to ourselves, it seemed. As we stepped down the slick trail among the old-growth conifers, descending to the rush of Balch Creek, we noticed a large enclosure. A sign told us it was the home of Aristophanes, the resident raven. But Aristophanes was nowhere to be seen.

We reached the creek and took shelter in a grove of giant trees, pausing to speak aloud some words to Dean. After a while we found ourselves drawn down the path to a small pond bordered by a wooden pavilion. As we entered the open-sided structure, facing the pond, we became aware of a slender man with waist-length braids, behind us, bending to the ground just off the deck. On his heavily gloved arm was a large blue-black bird: Aristophanes.

This long-time Audubon volunteer who spends every Wednesday visiting with the eight year-old rescue bird was gathering wet leaves to tidy up the large glops Aristophanes had left on the floorboards. Unaware of the reason for our visit, he began to weave a gentle spell that held us there for story after story about this remarkable bird.

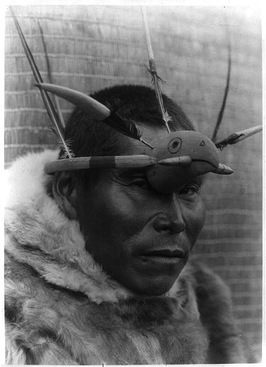

Edward S. Curtis photo of a Nunivak Cup'ig man with raven maskette

Edward S. Curtis photo of a Nunivak Cup'ig man with raven maskette As a symbol of death in European cultures, Raven has become associated with sadness, a bad omen. But in Africa, Raven is seen as a guide. In China and Japan, Raven is a messenger of the gods representing the light of the sun. Unlike the modern West which dichotomizes life and death into mutually exclusive realms, several indigenous cultures' creation stories depict Raven as both creator and trickster.

Our Audubon guide focused instead on his wonder at the intelligence of this bird, its neocortex proportionately thicker than a chimpanzee's. The raven not only uses tools, it makes them. Their communication skills, we're learning, are remarkably complex.

During his keeper's narrative, Aristophanes kept up a steady litany of gurgles, clucks (sounds like "tock!"), and croaks. This unexpected cross-species duo, showing up in this place of ancient beauty, on this most sacred of mornings, provided a glimpse of the power of the mythic imagination to connect us to worlds outside the limits of our physical existence.

As the life-force began to ebb from this deeply decent, loyal man, I was reminded with my every breath how each grief touches the ones that came before. With me in the room with Dean: my own father, whose brain cancer showed up 16 years ago this month. My dear friend Marcy, whose birthday we'll mark on March 25th without her. The other beloveds, mine, and those of the clients I serve. And beyond them, the names we'll never know, the generations of life in all its forms whose deaths made my existence possible.

All of them here, as memories, as felt presence, in the molecules we breath and the food we eat and the ground we stand on. In what John O'Donohue calls the space between us. I created the Death Talk Project to serve and support that space between us. Please let me know what you think.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed