We'd seen many prostrations already, in our ten days in Bhutan. Even our guide, who professed not to be religious, observed the ritual upon entering every temple. These prostrations commit the entire body, hands cupped together above the head, traveling to the forehead, to the mouth and heart, and then to the ground as the body follows from standing to kneeling to fully bowed. The former semi-pro athlete in our group likened them to burpees.

This particular encounter was on a trek to a yak pasture at 12,000 feet where we would sleep at the base of a monastery tended by a single monk and his cat. His daily prayers included a smoke blessing to keep the mountains clear for trekkers. Of greater importance were the other acts of intention that kept this remote hillside perch, funded by the government and staffed by monks on three-month tours of duty, available for pilgrims year-round.

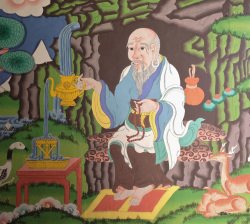

Besides supporting over 40 major monasteries and countless tiny outposts, the Bhutanese government acts as steward of the sacred by promoting, even requiring, active preservation of their culture. Cameras are not allowed in temples; what's within is to be experienced, not commodified. National dress and traditional architecture evoke a clear sense of belonging, of place, of connection to community in present time and through the ages.

It's not Shangri-La, of course. There are problems, contradictions, restless youth. But that sense of the sacred in Bhutan is palpable, able to be touched and felt. The prayer wheels on every stream of water; the 108 white funeral flags planted for every death; the tiny handmade stupas made of cremated beloveds, tucked into every cranny; the colorful karma-boosting prayer flags flapping everywhere the breeze will catch them. Those engaged in these practices might not be religious; observance may be spiritual, philosophical, superstitious, cultural, habitual. I'm not sure the distinctions matter when considering what's clearly a way of life.

It would be easy to disparage our own Western culture, by contrast, as hostile to the sacred, devoid of much collective connection to devotion or the divine. What strikes me most, though, as I reflect on my three weeks in Bhutan and Thailand at the tail end of 2013, is how many Americans I know who act as stewards of the sacred.

In my next post I'll tell you more about what I've discovered locally on my homegrown pilgrimage to find and create more meaning, more connection, near and far.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed