"The facts of death, like the facts of life, are required learning," writes Thomas Lynch, the literary undertaker.

Too few of us, these days, grow up learning the facts of death.

In a recent interview Stephen Jenkinson breaks this poverty down into three of its primary faces:

- We no longer have a shared understanding of what happens to us when we die.

- We no longer understand, culturally, what dying asks of us.

- We have hardly any lived relationship with those who came before us, our ancestors.

Attending four memorial services in the past week (and officiating three of them) reinforced for me the importance of these ceremonies not just in comforting the bereaved, but in establishing a relationship that bridges the gap between the living and the dead.

Many funeral and mental health professionals speak of "closure"; of accepting the reality of the death that occurred. As Lynch puts it, "seeing is believing; knowing is better than not knowing; to name the hurt returns a kind of comfort; the grief ignored will never go away.... The light and air of what is known, however difficult, is better than the dark."

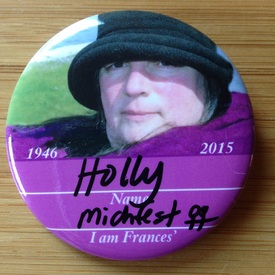

the spectacular Frances Wasserlein

the spectacular Frances Wasserlein All the ways we keep a place set at the banquet table of our lives for those who came before us: The lighting of six memory candles at a memorial that will be relit in six separate households going forward. Pebbles and petals from a beachside scattering ceremony that carry the potency of the day into other settings. The commemoration of the 60th anniversary of a sister's birth in the year after her death. The gathering of hundreds of mourners from two countries and many communities, bound into one people with memorial nametag buttons.

Our ancestors are more than our most recently deceased, of course, far more than those few whose names and faces we'll ever know. But the ways in which we honor and stay connected with those who die on our watch seems a decent starting place for the ancient relationships most of us in North America no longer know how to access.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed