Photo by Clayton Cotterell

Photo by Clayton Cotterell Published in Reed Magazine Volume 93, No. 4: December 2014

If you knew your death would come when you finished reading this article, you might greet it like Anne Boleyn at the block: accept your fate with courage and dignity, pay the executioner, and die with one stroke of the blade. You might also read very slowly.

The truth is that until it’s imminent, few of us are willing to contemplate death—and even fewer to talk about it.

Holly Pruett has taken the subject out of the closet and made it the centerpiece at her PDX Death Cafe, where people gather to consume sugary desserts and discuss shuffling off the mortal coil.

In a Portland park, strangers gather, six to a table, to experience their first Death Cafe. A woman shares that she started thinking a lot about death after being diagnosed with cancer. Another recounts a wake where children played near the open casket of their kindly grandfather. A man relives the fiery, ghoulish nightmares he had after viewing his grandfather’s corpse when he was a child.

It may sound like a scene from the film Harold and Maude, but the notion of folks coming together to discuss death gained steam 10 years ago when Swiss sociologist Bernard Crettaz began hosting what he called the Café Mortel. Attendees talked about the nature of death, and how our fear of it informs the way we live. In an age of tweets and text messages, these conversations proved engagingly authentic. Frothy “I am here” postings on social media and sound-bite news stories felt mundane and fleeting compared to something so profound and final.

In 2011, Londoner Jon Underwood established the Death Cafe franchise, providing open forums for talking about death while eating cake. (The cake is supposed to help people steady their nerves.) The not-for-profit events have no structure, themes, or guest speakers, and are not intended to provide information or grief counseling.

Bucking the conventional wisdom that people don’t wish to talk about death, Underwood discovered legions eager to discuss one of life’s crowning experiences. The declining influence of organized religion in people’s lives may contribute to the Death Cafe’s rapid growth. There are now more than 900 Death Cafes in 19 countries. But Underwood suggests that another factor spurring interest is the baby boomer generation coming to the top of life’s escalator.

“That’s the generation that has had the best services throughout their lives,” he says, “and I don’t think they’ll settle for second-class services when they come to the end of their lives.”

Holly Pruett radiates the clear-eyed conviction of a cleric. Three of her female relatives are Presbyterian ministers, and though she operates outside of that paradigm, she often describes her work as being like a secular chaplain. As a “life-cycle celebrant,” she weaves her client’s stories, beliefs, and traditions into ceremonies that commemorate major life events.

“Celebrations connect us to each other, to our community, and to the meaning in our life, which we can often skate behind,” Holly says. “When it is done well, ceremony allows us to bring the sacred into our lives—whether or not you use that word.”

Because humanity continues to cross the same thresholds, acknowledging these passages gets people outside their own story to connect both with those who have come before and those that will follow. Nonetheless, Holly says that the ways we approach funerals, births, marriages, and deaths have become formulaic and overly commercial.

“The needs are timeless,” she says, “but the conventional ways they are being met have become anachronistic and stale.”

Using skills honed as a student at Reed, Holly uncovers narrative needing to be strengthened, transformed, released, witnessed, remembered, affirmed, grieved, or memorialized. She suggests a path of inquiry to get there, and often officiates at the resulting ceremony.

Attracted to Reed for its academic rigor and counterculture reputation, she moved from New Haven, Connecticut, taking to Portland “like a duck takes to water.” She chose history as her major, and wrote her thesis on the 1905 Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition.

During her senior year she volunteered at the Portland Women’s Crisis Line, and after graduating took a job at a women’s shelter. Facilitating peer-led sessions, she witnessed the power that comes from hearing someone else’s story.

“I wasn’t there to solve any problems or provide answers,” she says. “But I could hold up a mirror and reflect back images of the women as capable, worthy, and intelligent that were different from the reflection that the abuse had shown them.”

At 25 she took a break and traveled through Europe and Southeast Asia, during which time she came out as a lesbian. By the time she returned to Oregon the state was embroiled in a battle over Measure 8. Sponsored by the Oregon Citizens Alliance, the 1988 initiative repealed Governor Neil Goldschmidt’s executive order banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in the executive branch of state government. Holly joined in the fight, and though voters approved the measure, she got an education in how the advocacy process works at the ballot.

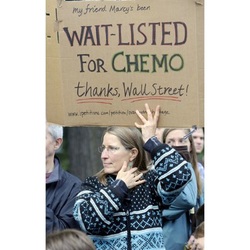

Entering the world of Salem politics, she took a job as a lobbyist for the Women’s Rights Coalition, followed by a stint as director of the Oregon Coalition against Domestic and Sexual Violence, a statewide coalition of women’s shelters and rape hotlines. For nearly 20 years she worked as a leader in the nonprofit sector and behind the scenes in advocacy campaigns. Then, in her late thirties, her father was diagnosed with cancer.

“The theme in my life had been losing my father,” Holly says. “First it was his work, then a four-year affair culminating in a 6,000-mile relocation just six days after my parents’ divorce. He never came back.”

Holly helped care for her father and lived with him the last summer of his life. But when he died 18 months after his diagnosis, her stepmother was too exhausted to go through the ordeal of a funeral. She had the body cremated and sent Holly some of his ashes in a yogurt container.

“I had to figure out for myself some kind of ritual that would help me,” Holly says. “I realized later it was less a memorial for him and more a rite of passage for myself, fully becoming a fatherless daughter. That’s what really set me on the path.”

A door had closed, but another opened and Holly stepped forward on a path of new professional engagement.

“I was raised to get to the level of highest impact,” she says. “Why be a teacher when you can be a principal? I had developed the strategy that could bring 5,000 people to the state capitol or affect the biennial budget, but I wanted to be more personally and directly involved with the important things in people’s lives.”

A friend shared a magazine story about a green burial preserve in South Carolina and suggested they bring the idea to Portland.

In natural burial, human remains are interred without being embalmed or entombed in a vault or liner. Placed in a shroud or biodegradable casket, the body simply decomposes into the earth.

In America, embalming gained currency during the Civil War because it enabled the interment of dead soldiers back home. Tens of thousands viewed the fallen president as Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train progressed from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois. In more than a dozen cities people filed past his casket and marveled at the preservation of the corpse, establishing a precedent for creating a focal point for the funeral.

Holly was working with Portland’s River View Cemetery to offer natural burials—concurrently taking instruction in funeral celebrancy—when she first heard of the Death Cafe. Approaching several other Portland practitioners, she suggested they give it a try.

Why don’t we talk about death and dying?

We live in a death-phobic culture where the end of life is seen as a failure rather than an achievement, Holly answers. Everyone recognizes the difficulty of giving birth and being born, but few honor the work it takes to die. In one century our society has progressed from families laying out their dead in the parlor to what Kenneth Hillman, professor of intensive care at the University of New South Wales, Australia, calls “ICU conveyor belt death . . . where even doctors don’t feel comfortable talking about death and dying.” Studies show that almost half of the cost of health care is spent in the last six months of life.

“We want people to be medicated and shunted off so that we don’t see the work that it takes to die,” Holly says. “We don’t have the opportunity to learn from it.”

PDX Death Cafe has drawn attention for the large numbers it attracts. It isn’t unusual for Holly to receive 100 requests for an event that can accommodate 80. In other parts of the country, events typically draw between 15 and 25 people.

Jeremy Appleton ’88 attended an alumni reunions Death Cafe hosted by Holly. He points out that some Buddhist sects contemplate death as a profound spiritual practice. The more we talk about and reflect on death, the less we are afraid of it, Jeremy says, but he finds this easier to do in the company of others. Listening to the myriad perspectives at a Death Cafe can induce a taboo-breaking exhilaration.

“As long as I fear death, I am not living life to its fullest,” Jeremy says. “By attending a Death Cafe, actively contemplating death, and making its reality more fully conscious, I endeavor to overcome my fear.”

Holly likens the experience to chatting with a stranger during a layover at an airport. Intimacy is easy when you don’t have to worry about any consequences.

“From my experience, I find it real and intimate that people are able to connect around this common humanity,” Holly says. “It’s not necessary to have expectations about that going further.”

“We live in an amnesiac culture with very little connection to our lineage and what came before us,” Holly says. “There’s no sense that there’s a future to be tended by making our stories available so that others might study them. Our stories show we matter and made an impact—that there was a space we occupied and the shape of that space can still be acknowledged.”

At a PDX Death Cafe picnic, people were invited to come early to complete a checklist of activities preparing them for death. They were asked to think about how they would like to die, in what surroundings, and with which people present. One man stalls in his progress and a facilitator approaches to ask if she can help.

“I’m still not certain that I’ll ever come face-to-face with the Grim Reaper,” he jests.

“I’ll give you better than even odds that you will,” she smiles.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed